March 9, 1862. A low, lurking shape steams out of Norfolk Navy Yard to finish off its damaged opponents from the previous day's battle. As the Confederate CSS Virginia - once the USS Merrimac - comes within sight of its target, another shape stands in its way: the Union's USS Monitor. The first naval duel of the modern age is here.

This story starts at the very beginning of the Civil War. When Virginia seceded from the Union in April 1861, the U.S. Navy was forced to abandon the naval yards at Norfolk. As they did so, they burned or sunk any ships they could not carry off. One of the burned ships was the screw frigate USS Merrimac - a ship with both a steam-powered propeller and a full set of sails. She had been burned while still at anchor, but the fires only went down to the waterline and her engine was still intact.

The Confederate Navy immediately faced enormous disadvantages compared to the Union's fleet. The major shipbuilding facilities were all in the north, and the nation's seamen came almost exclusively from New England and the Mid-Atlantic. Most of the Navy's rank and file had stayed loyal to the Union. The Confederacy didn't have many ships, men, or officers for their new Navy. Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory, however, decided that they could overcome these issues through quality. Creating a series of armored ships could break the Union blockade and keep the Confederacy's coasts clear.

Armored ships had been virtually impossible in the Age of Sail due to their weight and seaworthiness, but the rise of steam power caused naval architects to take a second look at so-called "ironclads." The first experiments with armored ships had already been tried in Europe. After the experiences of the Crimean War, with ships unable to survive extended contests with heavy land-based artillery and explosive shells, the French and British had both launched ocean-going ironclads. The French launched La Gloire in 1860, and the British launched HMS Warrior in 1861. La Gloire was wooden-hulled with iron plating, but Warrior was completely metal. Still, both were conventional designs with high sailing masts and open decks. Even though both were immediately famous, neither one had ever seen action.

Mallory's problem with building an ironclad was that there was no factory in the Confederacy that could build a steam engine for a ship - there were several in the North (which goes to show how badly behind the South was industrially). In desperation to get an operational ironclad as soon as possible, Mallory decided to use the burnt-down hull of the Merrimac. Naval teams towed it into the Norfolk Navy Yard, had a new armored deck laid, and built an angled casemate on top, iron plating laid over a wooden infrastructure. 14 guns poked out from this casemate, but they were only armed with explosive shot instead of armor-piercing. No one expected the new ironclad to fight anything but wooden Union ships.

Rechristened as the CSS Virginia, the new Confederate ironclad caused a stir in the North as it was being constructed. Militaries of the 19th Century were not very good at keeping secrets, and intelligence soon trickled back to Washington and Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln directed Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles to begin constructing their own ironclad. Welles set up a board to consider designs, and of seventeen that were submitted only three were approved for construction. Of the three, only one was completed in time - the work of Swedish immigrant and inventor John Ericsson.

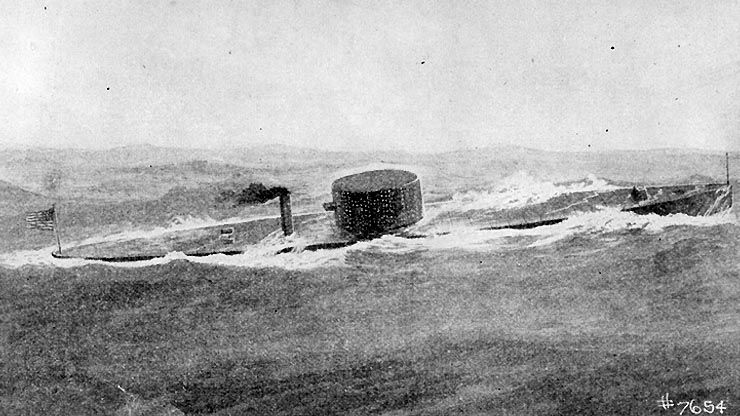

Ericsson's design was radical. Unlike the Virginia/Merrimac, which had many smaller guns, Ericsson chose only two large guns for his ship, but placed them in a cylindrical turret powered by its own separate steam engine. A rotating turret was a completely new idea, untried by any other navy. The shallow draft and weight of the armor convinced many that it would never work, and Ericsson's design was derided as a "cheesebox on a raft." It looked like nothing more than a piece of driftwood with a tank turret on top.

Welles approved Ericsson's design, though, and the Confederates soon learned that the Yankees were building an ironclad of their own. They decided that the North would never get their ship ready in time to fight the Virginia - but as a precaution, they decided to fashion Virginia's prow into a ram, in the style of ancient Greek triremes. February 17, 1862 saw the Virginia finally commissioned and ready for duty. Under the command of Captain Robert Buchanan, who was itching for a fight, Virginia planned to steam out as soon as possible and attack the Union fleet stationed in the Chesapeake Bay at Hampton Roads.

On March 8, 1862, Virginia ground out with a number of small wooden ships in its wake, cutting a low and deadly line across the horizon. The Union ships tried to maneuver and catch the hulking beast in their crossfire. Virginia horned in on the USS Cumberland and the USS Congress. As their shots bounced off the iron plates of the Confederate vessel, Virginia collided ram-first with the wooden Cumberland. It almost destroyed them both, because the ram got stuck in Cumberland's hull and the Union vessel almost dragged her down with it. As Virginia broke free, her ram was pulled off with the sinking Cumberland.

Virginia turned on Congress and another nearby ship, Minnesota. Buchanan poured fire into Congress, which was soon ablaze, and forced the USS Minnesota aground. Since night was fast approaching, and the Virginia had suffered a fair bit of damage - Buchanan had been wounded, several armor plates loosened, and her smokestack nearly falling off - Buchanan decided to call off the attack until tomorrow. He could finish off the Minnesota then.

When news of the fight reached Washington, there was nearly a panic. Virginia had destroyed two ships, grounded another, and slunk away barely damaged; some people anxiously looked out their windows, expecting to see her steaming up the Potomac. The whole East Coast could be open to attack: New York, Philadelphia, Boston were vulnerable to a ship that could not be beaten. Lincoln's Cabinet met, and with multiple Secretaries panicking, only Lincoln and Navy Secretary Welles were calm. Welles took this moment to drop a bombshell: the Union had its own ironclad - and it was on its way.

Lieutenant Catesby Jones, the man who had supervised the Virginia's construction, took charge of her on March 9, 1862, when he moved out to finish off Minnesota and begin the expected rampage across the Atlantic. All he had to do was - what was that? That, on the horizon?

A cheesebox on a raft, you might say.

Virginia fired at Lieutenant John Worden's Monitor, and the battle was on. For three hours, the two ships circled and hammered away at each other. The Virginia had no solid or armor-piercing shot, so its shells exploded harmlessly on the Monitor's hull. The Monitor was firing its guns with only half charges so not to damage the hull integrity, so its shots did not have enough stopping power to penetrate Virginia. Even as these two ships circled, other wooden ships fought around them, trying to knock each other or the ironclads out of action. Monitor's smaller size made her far more nimble; it took Virginia almost 45 minutes to complete a full turn, but she had more guns.

Finally, the battle paused briefly when some fragments of shell struck Worden in the eyes, temporarily blinding him. The Monitor drew off, preparing to recock and come back for a second round. However, Jones saw the Monitor pull away, figured he had won, and pulled back to Norfolk to fix his own considerable damage. The Clash of the Ironclads was over. It was claimed as a victory by both sides, but by any serious metric it was a draw.

What was the outcome of all of this? Not much in the short term. More Union ships soon arrived in Chesapeake Bay, including the two other Union ironclads. Even as Union troops began landing at Fort Monroe to march towards Richmond, the Virginia remained in port. Monitor and Virginia glared at each other from across the James River, one at Newport News and the other at Norfolk, but neither ever engaged each other again.

In fact, neither ever fought again at all. The Confederacy was forced to abandon Norfolk in May 1862, and Virginia's draft was too deep to escape up the James River to Richmond. The Navy decided not to let her be captured, so the Virginia was blown up on May 11, 1862. Monitor was sent to do coastal duty on the Carolina shore, but was caught in a storm and sank, though most of her crew were saved, near Beaufort, North Carolina on December 31, 1862. Neither had lasted a year.

The whole world was fascinated by the ironclads. In the Union, many more ships were built on the Monitor design, and served throughout the war on the Mississippi River as well as on the coasts - the Monitor design proved ill-suited to the open seas. All over the world, other navies emulated the Monitor, including the Russian and Swedish Navies. Several fought in the naval battles of the 19th Century, including South America's War of the Pacific and in the Spanish-American War. The global excitement became known as "monitor mania."

A new age of naval warfare had come, and the world would never be the same. Instead of wooden ships, high masts and creaking oak, the experience of the navy would now be steel, sweat, and steam.

The Monitor's wreck was discovered in 1977, and pieces have been recovered ever since. Some are on display at the Mariners' Museum in Newport News. Some of the skeletons of the drowned crewmembers were identified, and laid to rest in Arlington in 2013. Finally, the Mariner's Museum completed a full-scale static replica of Monitor in 2005 - also in Newport News.

In 2010, my then-girlfriend and now-wife Margaret took me to the Mariner's museum. There was a bell on the Monitor replica. I, being a 19-year-old history nut, rang the bell enthusiastically. She was embarrassed at my goofiness, not for the first or last time.

I basically told the entire story just to put that event into context.

Book Recommendations: James M. McPherson's recent War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies (Raleigh: University of North Carolina Press, 2012) is an excellent overview of the naval war, including Monitor v. Merrimac.

留言